Legal Issues

The law that applies to grandparents also applies to other non-parent relatives. This information should not substitute seeking legal advice from an attorney for your specific situation.

For the purpose of this page, the following definitions apply:

- “Grandparent” will always include aunts, uncles, cousins, siblings, great-uncles, etc., (even stepparents who have not adopted their spouse’s or domestic partner’s children) unless the guide says otherwise.

- “Parent” or “parents” will always mean the parents of the minor children the grandparent or other relative is concerned about.

- “Child,” “children,” “grandchild” or “grandchildren” will always identify the minor children the grandparent is concerned about.

Generally, a child’s birth mother is the child’s legal mother (unless the birth mother is acting as a surrogate) until the child is legally adopted by another person or the birth mother’s parental rights are terminated by the state. Whether a man is a child’s legal father is sometimes more difficult to determine. The husband of a woman who gives birth to a child during their marriage is presumed to be the legal father of the child (unless he or the woman later proves otherwise). He is still considered the legal father if the child was conceived by artificial insemination. A man who signs an official state form acknowledging he is the father is presumed to be the father of the child. A man who legally adopts a child becomes the child’s legal father. In a paternity case, the court can determine whether a man (married to the mother or not) is the legal father of a child.

The state can terminate parental rights, making the mother and/or father no longer the legal parent of a child. Mothers and fathers can also give up their parental rights by agreeing to allow someone else to adopt their children.

Stepparents and same-sex spouses who have not adopted their spouses’ children do not have parental rights. Under Oregon law, stepparents have rights similar to those grandparents have.

Under Oregon law, a grandparent who becomes responsible for the care of a child when parents are away may be able to get medical and dental care for the child and enroll the child in school without the parents’ approval in some situations. The grandchild must already be living with the grandparent. The grandparent also must try in good faith to contact at least one of the parents to ask for consent for medical care or for admission to school, or be able to explain why he or she couldn’t contact the parent. The grandparent must then fill out an affidavit and sign it in front of a notary public. A sample form, affidavit of relative caregiver, is available here. This affidavit will expire one year after you sign it. You can get a new one if the parents’ consent still can’t be found.

You can present it to medical and dental providers and to schools once you have signed the document. Get legal advice right away if the provider or school does not accept the form. Immediately tell the providers and the schools if the minor child stops living with you. This affidavit will expire one year after you sign it. You can get a new one if the parents’ consent still can’t be found. Providers can hold both you and the parents responsible for payment for services, but you also have the right to be reimbursed by the parents if you pay.

How to complete the form:

- In the first three blanks, type or neatly print your full name, your Oregon driver license or state identification number, and the date of your birth.

- List your relationship (grandmother, etc.) to the children, then list the full names of the children and their dates of birth. These children must be living with you. State the address where you all live.

- List the full name of at least one of the legal parents or legal guardians of the children, and that person’s last known address and phone number. Put your initials on the short line before the person’s response when you contacted him or her or them or, if you couldn’t locate the person, put your initials on the short line before that information. Do not initial BOTH.

- Sign this document before an Oregon notary. Be sure to have picture identification with you.

Both legal parents, married or not, have equal rights over their children unless a court gives one greater rights than the other.

Either parent can take the children from a non-parent on demand if there is no court order giving one parent specific times with the children. You do not have to turn children over to their father if a current court order says your daughter has the right to the children during the time you are babysitting.

Oregon’s Department of Human Services Child Welfare has a duty to intervene in cases of child abuse and neglect. Unfortunately, it is virtually impossible to get an agency investigator onto the scene in the time it takes to put children in a car. The parent has the right to take the grandchildren with them unless there is a court order that keeps the parent from taking children under circumstances like these.

A grandparent who does not have legal custody has no more authority over a child than a stranger would have. Unless one of the parents gives you permission, you usually can’t authorize medical or dental care for a child. (In emergencies, hospital staff are allowed to provide life-saving treatment and other major medical procedures, but they can do nothing beyond that without permission.)

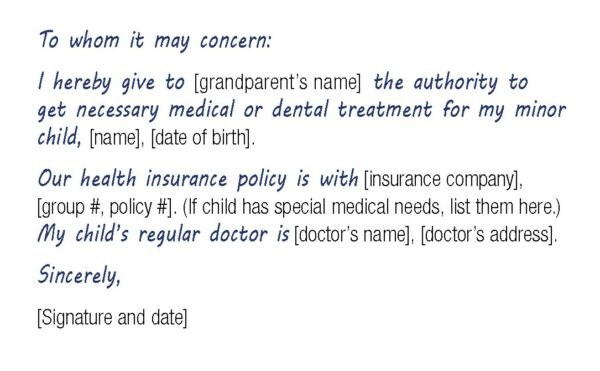

The simple solution is to get written permission from one of the parents. It can be handwritten and include only the date, the name and birth date of the child, the name of the person authorized to get care for the child, and a statement that the parent permits the person to authorize necessary medical and dental care.

If you have written approval to care for your grandchild through a power of attorney, you also have the ability to authorize medical care.

Children who are at least 15 years old can consent to their own medical and dental treatment without parental consent, and Children 14 years or older can consent to mental health and chemical dependency treatment without parental consent. For more information on minors’ rights to consent to health care, please see “Minor Rights: Access and Consent to Health Care” at https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/HEALTHYPEOPLEFAMILIES/YOUTH/Documents/minor-rights.pdf.

Oregon law protects children living with non-parents by requiring school districts to allow children to attend school in the district where they reside.

School districts sometimes resist admitting some children, suspecting families give false addresses just to get their children into a better school.

Oregon Revised Statute 339.133 states, “Individuals between the ages of 4 and 18 shall be considered resident for school purposes in the school district in which their parents, guardian, or persons in parental relationship to them reside.”

Be prepared to show you are in a parent-child relationship when you go to the school to register your grandchild. This proof is easy if you have a court order showing the child is supposed to be living with you.

Otherwise, a temporary power of attorney for childcare signed by a parent and your records of how long the child has lived full-time with you, or information about the reason the child is living with you, should satisfy the school. The power of attorney form alone is not enough proof. You may find it necessary, if the parents do not cooperate, to show the school a relative caretaker affidavit.

The records you use can include:

- Letters (including the envelopes) the child has received at your home;

- Receipts for bills you have paid for food, clothing, and health care;

- Notes from witnesses (such as your neighbor or your landlord, and the child’s parent or other relatives); and

- Utility bills and phone bills that have been higher because you have someone new in your home.

You may have a hard time proving the children live with you if they have just moved in. You may need to show school personnel a copy of the wording of ORS 339.133. A lawyer may need to talk to the school in some cases.

Temporary Power of Attorney:

Oregon law provides a special temporary power of attorney parents can use to give others the right to take care of their children for up to six months at a time.

The parent can give you authority to make decisions about medical care and enroll the child in school using this kind of power of attorney. Unless the parent puts limits on what you can do in the power of attorney, you can exercise all of the parental rights the parent has except the right to agree to the marriage or the adoption of the child.

No court involvement is necessary to obtain this power of attorney or to end it. The parent can stop sharing power without needing a reason, even before the six-month limit of the power of attorney is reached. The parent has the right to get the children back at any time.

For military families there is a special power of attorney that will last longer than six months, and is valid for the length of deployment plus 30 additional days.

How to fill out this form

- In the first two blanks of this model form, type or neatly print the name of the parent who will sign over the power, followed by the city where the parent lives.

- In the next two blanks, put the name of the person who will get the power and the city where that person lives.

- Fill in the names and dates of birth of all of the children involved.

- Next, have the parent take the form, with photo identification, to a notary public to sign the form and have it notarized. Notary publics can be found in most banks, real estate offices and law offices. Some charge for their services. Note: If the parent is in another state, that state may have a specific form the parent should use instead. If no specific form is required there, the sample form here should be changed to show the state where it is signed and notarized.

- The parent gives the completed form to the person who will act as the caregiver — that is, the “attorney.”

- For the parent who is going on active duty, slightly different language will be needed in a temporary power of attorney for childcare.

- At the beginning of the form, where the parent states his or her name, the parent also should identify himself or herself as a member of a specific branch of the U.S. military.

- In the section of the form that says how long the power is to last, the military parent should say that “The power designated above is delegated for the period until [the date the deployment ends, if known]/[a period not exceeding the term of active duty service, if the ending date is not known], plus 30 days.”

One option for longer-term caregiving is guardianship. A guardianship can give you more power over the child than can a power of attorney. A parent cannot decide arbitrarily to take the child away when a caretaker has guardianship. A judge would have to agree that returning the child to the parent is appropriate. Oregon’s law about financial support for children also applies to guardianships, and you would be entitled to seek child support from both of the parents while you are taking full-time care of the child. (You may not get financial support if the parents have no income, but the law makes it possible for the state to force payment when there is income.)

Guardianship requires the filing of court papers and the signing of an order by a judge. It does not necessarily mean a “court battle.” The parents can give written consent to make you the child’s guardian when you file the court papers, and the process will not take long. When the child may be a tribal member or eligible to be a tribal member, it will be necessary to communicate with the tribe about the case.

The parents (or you) can have the guardianship ended by a new court order once the problem that gives rise to the guardianship has been resolved. The guardianship will end by itself when the child turns 18 if there is no further legal action.

There are some potential financial drawbacks to becoming a child’s guardian, especially for people with moderate or middle incomes. The child may need medical care, for example, and the guardian may not have access to health insurance that covers the child.

To establish a guardianship without the cooperation of parents, you must be able to show you had a “parent-child” relationship with the child for a period at least part of which occurred within the six months before you file your petition for the guardianship. The law defines a “parent-child” relationship this way:

- You have or had physical custody of the child (the child lived with you without the parents) or you lived in the same household as the child (with one or both of the parents or with other people).

- You provide or provided for the necessities of life for the child (food, clothing, care, education, religious training, etc.). You can do this by providing these things physically or by providing money for someone else to do this physically.

- You do or did have day-to-day interaction with the child (not just babysitting on weekends).

- The relationship with you fulfilled the child’s physical and psychological needs for a parent.

How do you count the required six-month period? Here are some examples:

- If the child has been living with you (with or without others) during the last six months and is still living with you, you can file now.

If the child moves out, you can still file during the next five months

- If the child lived with you until five months ago, you can file now, but it will be too late to file (unless the parents agree in court papers to your becoming the guardian) after another month goes by.

You also must persuade the judge, based on the evidence, that it is more likely than not the legal parent is currently not acting in the best interests of the child (because of abandonment, instability, abuse, imprisonment, addiction, etc.). You must then show it is in the child’s best interest for the child to have you — rather than someone else, such as the other parent or a different relative — as the child’s primary caretaker.

The judge must look at these questions when evaluating the case:

- Is the legal parent unwilling or unable to care adequately for the child?

- Are or were you recently the primary caregiver for the child?

- Would it be harmful for the child if you were not made the guardian of the child?

You need to weigh the pluses and minuses of going to court just as in a case to obtain the right to contact the children.

When Oregon law mentions the word “custody,” it may be talking about more than one thing. Custody sometimes means actual custody — the children are actually living with someone regardless of who has legal rights over them. It may mean legal custody, which is the court-granted right to make decisions over children’s schooling, medical care, religious training and other basic choices on behalf of the children. Legal custody can often include physical custody — the right of someone to have the children live with them.

Custody and guardianship differ from each other in one important way. Courts look at most guardianships as temporary, no matter how long they last, because a guardianship can end when the problem that gave rise to it has been resolved. Courts look at custody as a permanent situation. Once someone has obtained legal custody over children, anyone else — even a parent — must show it is not in the children’s best interest to continue that situation. Ending custody is harder than ending a guardianship.

A legal custodian can approve a child’s marriage or adoption. The custodian is also entitled to financial support from the parents on behalf of the child.

The standards the grandparent has to meet to get custody are the same as a guardianship.

Because custody is theoretically permanent, a grandparent should expect to show the parent is likely unwilling or unable to look after the best interest of the child both now and in the future.

A child who has little income or few resources may be eligible for ongoing health coverage and a small amount of cash assistance from the state. The child may still be eligible after the child becomes a member of a grandparent’s household, such as through the establishment of legal custody, if the grandparent’s income is low. The child may be able to get benefits through the Oregon Health Plan, too.

You have no way to protect yourself from otherwise lawful contact if the parent who is violent has done nothing to you. You can talk to a domestic violence shelter advocate about some practical steps you can take to prevent a confrontation.

A grandparent who receives threats — or worse — from a parent of the grandchildren should always report the incident to the police. It is also important to create a logical safety plan if finding a safe place becomes urgent. Local domestic violence shelter organizations can be very helpful for this purpose.

A parent who has been the victim of violence by the other parent may be able to get a Family Abuse Prevention Act (FAPA) restraining order from the court. The FAPA order will designate which parent will be responsible for the children. You should have a copy of the responsible parent’s order and tell the police if the other parent violates the order with regard to contact or time with the children. A FAPA order requires the violent parent to stay away from the spouse or other adult family-member victim. A FAPA order can force the violent person to move out of the family home. They can be arrested for violating the order.

You cannot get a FAPA order unless you were living in the same place with the parent who was violent or were seriously threatened with violence. A person who is at least 65 years old, or who has a disability, is likely eligible for a similar kind of restraining order for elderly or disabled persons. Both FAPA and elder-abuse protection orders are available at no charge to people who meet the requirements of the protection laws. Forms are available at the offices of court clerks, online on the state court website and from domestic violence shelters.

You also may be eligible for a stalking protection order depending on the behavior of the violent parent. There is no age limit or family-relationship requirement for stalking orders. Stalking orders can require someone to stay away from you even if there has been no violence. You simply have to show the person’s repeated behavior toward you has been intentionally threatening and frightening (stalking). Examples of stalking behavior include keeping watch outside a person’s home or workplace, placing harassing or hang-up phone calls, following a person, sending frightening letters, etc. There is no cost to obtain this kind of order.

People who violate restraining or stalking orders can be arrested immediately and, in some instances, charged with a new crime. It’s a good idea to talk to a domestic violence advocate or an attorney about how to get a stalking order.

Modest Means Program

Oregon lawyers created the Modest Means Program to help moderate-income Oregonians find affordable legal assistance. The program is intended to help those who earn too much to qualify for legal aid, but who cannot afford traditional legal fees. Modest Means lawyers have agreed to charge reduced rates for legal work provided to clients referred to them through the program. There is no grant, fund or subsidy that makes up the difference between the lawyers’ regular rates and the Modest Means Program rates. The lawyers agree to charge reduced rates because they believe in the mission of this program and want to help.